making art downtown: a conversation with Pasco cafe owner Saul martinez

In the heart of Downtown Pasco lies a place where you can order a latte and leave with a new perception about what it means to create art. Owner Saul Martinez, art teacher and artist himself, has designed it that way.

Café Con Arte, was once a vacant building sitting right next to Peanuts Park, a flexible plaza and recent City investment. Every week, the plaza hosts the weekly farmers market, where hundreds of people buy and sell produce from eastern Washington's many farms. But during the week, it mirrors the rest of Downtown: it's a place that few choose to utilize, and some even avoid.

Framework's work to implement the Downtown Masterplan has been aimed at reversing this trend of inactivity through adaptive reuse of buildings, regular events, and better use of public space. Much of this work has been focused on updating codes and interpretations that create barriers. For example, when the Master Plan was adopted, a space like Saul's wasn't even legal — it took lifting parking requirements to allow the building to become a coffee shop. Of course, changing codes to allow new uses is just that start, and the community members like Saul, who are investing in Downtown Pasco, are at the core of its success.

We sat down with the cafe owner to talk about what drove him to quit a job where he could “finger paint all day if he wanted to” and plant roots in a Downtown that is struggling to ditch its reputation and blossom as a cultural hub. He talks to us about the potential for art to be a tool for youth empowerment in Pasco, and how he thinks the City could be support folks who want to take a chance Downtown. Enjoy an abridged version of our interview below!

Sitting Down with Saul

Saul cleared off a table full of art supplies to make room our recording equipment.

the origin of cafe con arte

FRAMEWORK:

You can introduce yourself however you want…

SAUL MARTINEZ:

My name is Saul Martinez. I am a Chicano artist and new business owner in downtown Pasco, Washington, which is on the east side of the state.

FRAMEWORK:

And we're here at Café con Arte, where you started this really cool thing in downtown Pasco. Can you talk about how this idea was conceptualized?

SAUL MARTINEZ:

Oh boy, those are kind words. I've been reflecting on this question a lot in the last eight months, and I used to just kind of simplify the answer to, "why not?"

I am an educator by trade, and so working with kids in this community, it just really broke my heart that they were embarrassed about the space that they were from — the East Pasco community.

When I first moved to Tri-Cities about 12 years ago, everybody was like, "Yeah, Tri-Cities is a great place to live and grow and raise kids. Just avoid East Pasco." And for the first two or three years, I actually listened to that advice. Even as a teacher here in Pasco, I would just never go to downtown East Pasco — until I did. And then it was just like, "Oh, why have I avoided it this whole time?"

It started with coming downtown more frequently with my art club. We were hanging Christmas lights and painting windows to beautify the area. And it was also just to put them out there so people could see that my New Horizons kids were amazing kids, because they are. I saw their aptitude. I saw their willingness to give back. It was just a beautiful thing.

There we would engage with all sorts of community members and leave with this impression of downtown Pasco as a diamond in the rough. Just somebody needed to activate it…

“The process that we use in the classroom—why can’t we use this in the community?”

From art teacher to cafe owner

SAUL MARTINEZ:

One thing that I noticed in my classroom was that the kids — even though they seemed to be proud of themselves — when they would talk, their body language spoke differently. You could see them walk down the hallways with a proverbial “tail between their legs.” They just seemed so embarrassed… My question in my classroom was: How do I change that? That was my focus mid-COVID.

I came to the realization that “dead art” wasn’t speaking to them. Why was I trying to teach them classical when all they cared about was hip hop, or country? So I started teaching them contemporary works, I started highlighting artists that were expressing their experiences in unique ways.

Immediately their conversations changed. They opened up a lot. They started talking about their own experiences. It was back and forth. No more monologue — we were having a conversation..

The process that we used in the classroom — why can’t we use this in the community? How can we further that conversation and start looking at ourselves through a lens of reverence, of being valued and celebrated?

That was that. Again, I went back to teaching and I thought that question would never resurface — until I met a person in the community named Alexia Estrada. Just a brilliant young lady with so much excitement about what this community could be.

She said, “I want a third space. I want a coffee shop in downtown Pasco.” We shook hands within the first 10 minutes and agreed that we were going to do something.

FRAMEWORK:

What I’m hearing is that you saw that contemporary art was missing from your student’s education but also from Pasco as a whole.

SAUL MARTINEZ:

Not missing, but maybe room for more.

If you look at more modern or previous art forms and movements, it was about capturing a moment. Contemporary art is more about speaking about our immediate needs — as individuals or as a community. It highlights what’s right, what’s wrong, and everything in between.

And as an artist, with great power comes great responsibility. It’s important to use your skill set to speak about the things happening in your community or beyond.

“‘Dead art’ was not really speaking to my kids. Why was I trying to teach them classical when all they cared about was hip hop, or country?”

“To Be Or Not To Be” by Periko the Artist, in acrylic and spray paint. Displayed at Cafe Con Arte in September 2024.

you caught me: I wanted a gallery

FRAMEWORK:

The room we’re sitting in has paper cups full of crayons, paint brushes, plants, chalk… Art is clearly happening here, it’s all over the walls. And before we started recording you cleared off the table, which had seemingly been the site of some kind of art making.

What’s happening here at Cafe Con Arte?

Saul Martinez:

You know, the big picture of Cafe Con Arte — I would call it a conceptual art piece.

If we go back to my kids and what I wanted them to see, I wanted to hold up a mirror and say, “Look at yourself. You are of value. You are worth anything and everything. You are visible, and I see you.”

I want that for the community, too.

FRAMEWORK:

From what I’m hearing, you saw this opportunity to nurture arts in Pasco, but you didn’t just open an art gallery, you opened a cafe…

SAUL MARTINEZ:

I wanted a gallery, you caught me. But I know what the art market looks like in the Tri-Cities, it’s almost nonexistent. You can count the galleries in the Tri-Cities – a population of 300,000 people – on one hand. How fair is that to a community? It’s embarrassing. I feel like it was a calling, a need. I wouldn’t say it was a dream, it was just like, I can’t go another day, another year, complaining about it. I have to do something about it.

The coffee shop? I have to pay the bills. In the Pacific Northwest, you can’t go a block without seeing a coffee shop, but drive around downtown Pasco and there were none. To me it’s a no brainer. And it’s just the beginning - I feel like, third spaces downtown – coffee, food, toys, games, books, events at night, that’s all going to be a part of it. It’s more than just coffee.

FRAMEWORK:

You’ve already been having art classes here, speakers… You’re doing a lot. What’s been the reception of those events?

SAUL MARTINEZ:

I’m trying a bit of everything… Just like we are teaching the community that we now have sit-down coffee in downtown Pasco, [we’re also] teaching people that paint-and-sips are a thing. People come in expecting paint-by-numbers, but that’s not what we do here! We’re gonna put you through a little stress because that’s growth, and you’re gonna love what you walk out of here with.

it’s time for us to be San Diego, Los Angeles, Santa Ana, Fort Lauderdale, or wherever… You can basically spin the globe, point, and find communities that have said enough! We can be who

we want to be!

PASCO’S IDENTITY AND VISION

FRAMEWORK:

Let’s talk about Pasco. Pasco has been working on changes downtown to make it a place where the culture is visible and people want to be. What makes Pasco’s culture unique?

SAUL MARTINEZ:

I think it’s the population, I think it’s the moment we’re in, where the community can choose what it wants to be. I don’t feel like it’s ever felt like it had the liberty to do so. For some reason it felt like it needed a top-down definition: This is who you are.

But with a 56% Latino demographic — maybe closer to 62% — it’s time for us to be San Diego, Los Angeles, Santa Ana, Fort Lauderdale, or wherever… You can basically spin the globe, point at it, and find communities that have said enough! We can be who we want to be! There’s no shame in that in fact, quite the opposite.

The Tri-Cities and Pasco, with this influx of transplants as well as people who have deep roots here, there’s this really cool opportunity.

FRAMEWORK: When you think about downtown Pasco and the changes you want to see, what does that look like?

SAUL MARTINEZ:

Vibrancy.

I want people to experiment with what a vacant lot can be. There’s so much repetition because it’s safe. I want people to take risks — throw that Hail Mary pass at a plant shop, or a tattoo parlor, an antique store — even if it might not work out in the immediate future.

People need those walking spaces between Café con Arte and the Italian restaurant right down the street. Another coffee shop, bring it! I think with more options, come more people, and more foot traffic… I welcome that.

I know what the art market looks like in the Tri-Cities, it’s almost nonexistent. You can count the galleries in the Tri-Cities – a population of 300,000 people – on one hand.

supporting third spaces

FRAMEWORK:

What could the city do to better support places like Café con Arte?

SAUL MARTINEZ:

Remove all restrictions. There are so many barriers, so many hoops to jump through. And when you get through those hoops you find mini hoops that you have to jump through.

There needs to be access – I’m sure there’s grants out there but as a one man show running Café Con Arte, by 11:30 or 12 a.m. when I’m done book keeping and it’s time to look for grants, I find myself asleep on the couch. There’s never enough time.

It would be great if someone had all the resources. I feel like a lot of organizations are doing similar stuff but they’re not connected.

And then there are the vacant lots — I can point to six vacant lots over here, three right next to me. I don’t think that attracts culture. I think we need to have these spaces filled, so looking at Vacancy Tax, or something like the program “Vacant to Vibrant” in San Francisco.

I think the City needs to be loud and clear about what they hope for from the community. I think they need to tell us that they’re stepping aside for creatives. I think we all have this creative nature about us, we are innovators. We just need to know that it’s a safe space for us to do so.

I have major faith in this community. There’s a lot of excitement and buzz around what Framework is helping to do and I think it’s only a matter of time.

“I think the City needs to be loud and clear about what they hope for from the community. I think they need to tell us that they’re stepping aside for creatives. I think we all have this creative nature about us, we are innovators. We just need to know that it’s a safe space

for us to do so.”

the plan

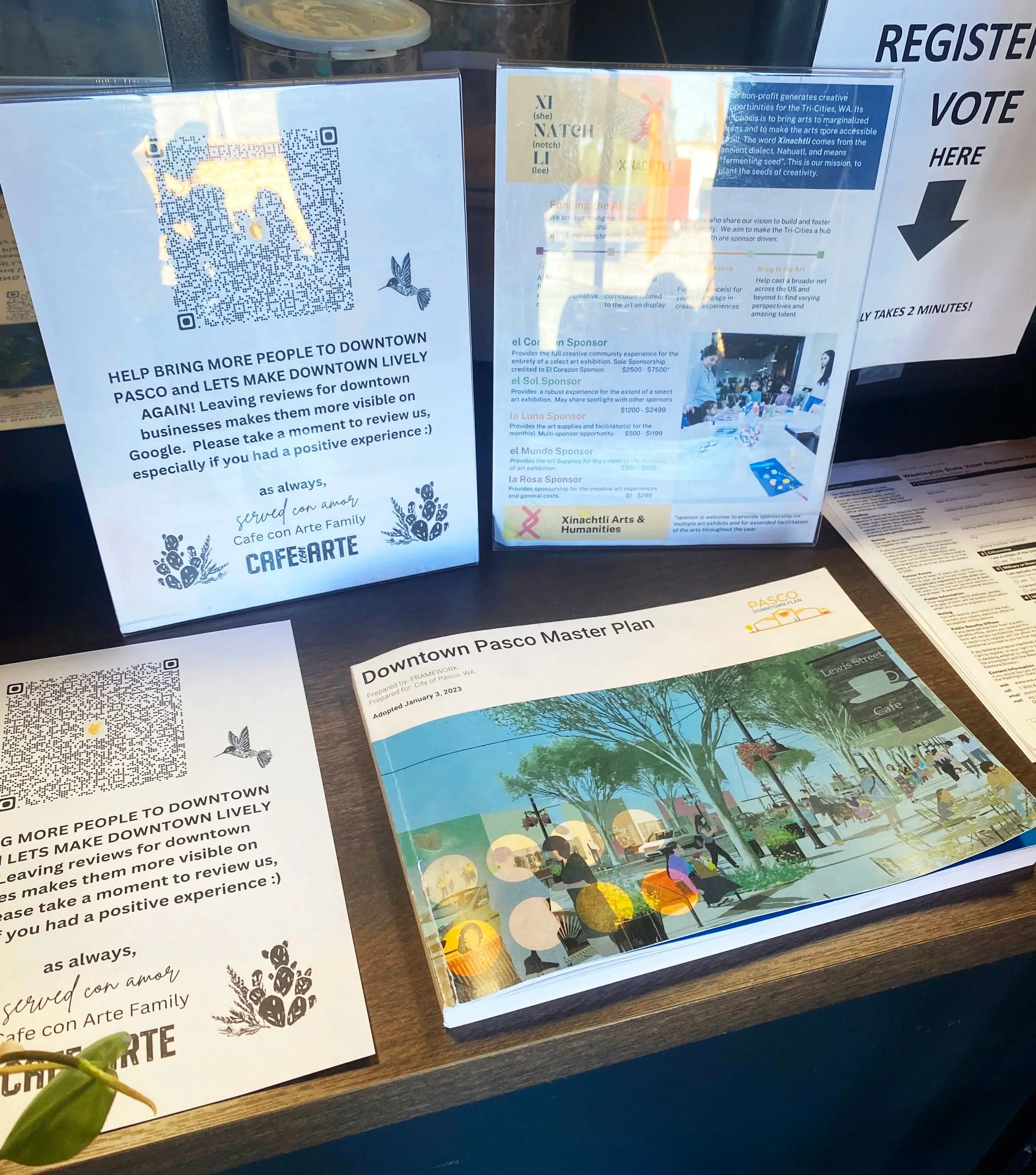

A copy of the Downtown Pasco Master Plan sits on the counter at Cafe Con Arte, reminding visitors that there is much in store for the future of Downtown.

Written by Hope Freije @Framework

What comes next? putting Pasco’s downtown plan into action

Framework had an exciting week at the Washington APA conference in Bellevue this past month! In addition to setting up an exhibit to share some of our recent projects and hosting two presentation sessions, we accepted an award for our downtown planning and implementation work with the City of Pasco. During the past few years that we have been working in Pasco, we have formed meaningful relationships with the community and have grown invested in the City’s success—we were honored that the project received an Excellence in Planning Award from the Washington Chapter of the American Planning Association (APA WA) and the Planning Association of Washington (PAW). We wanted to take a moment to talk about the process of writing and implementing this plan, and how we intend to continue to help the City achieve its goals through ongoing implementation efforts.

Award Ceremony

The team, including members from Framework and the City of Pasco, accepted the Excellence in Planning Award at the 2024 Washington APA conference.

downtown pasco

Downtown Pasco has many of the ingredients for a successful downtown: windowed storefronts lining 12’ sidewalks make for a walkable and engaging shopping experience; historic architecture creates a distinct character, including a brick post office and stucco former movie theater; more recently, the City invested in Peanuts Park, a central plaza with a structure for hosting weekly farmers markets.

Beyond the infrastructure, Pasco’s culture is also an asset to its Downtown. With a largely Spanish-speaking population and a strong relationship with its sister city Colima, Mexico, Pasco’s culture is visible in its yearly Cinco de Mayo Celebration and Fiery Foods Festival.

But between its weekly farmers markets and yearly festivals, Downtown often feels underutilized. Vacant buildings reveal a lack of investment. A lingering reputation as being unsafe deters people from choosing Downtown as their destination for social outings. And like many downtowns, it lacks housing and instead relies on commercial uses to generate foot traffic. These conditions make it difficult for local businesses to survive, furthering the cycle of disinvestment. The City decided to invest in a Master Plan to outline a strategy for reviving Downtown.

A Walkable Downtown

Windowed storefronts add interest along a fairly wide sidewalk.

Historic Architecture

Buildings such as the former Empire Theater create a mosaic of history and culture Downtown.

forming a vision

During public engagement efforts for the Downtown Master Planning process, people made it clear to us that they didn’t want a plan that would just sit on the shelves. They wanted to see a regular schedule of Downtown events, the addition of coffee shops and other places to spend time, and better uses of public space. They pointed out areas that could benefit from better lighting, decorative pavement, or pedestrian street closures to encourage more people to spend time Downtown. And they identified barriers such as outdated municipal codes and permitting processes, poor connection to the Columbia River, and a lack of services available for people struggling with poverty.

The engagement process was crucial not just for shaping the visions, goals, and strategies that formed the basis of the Plan, but for generating community capacity. Through the stakeholder meetings, visioning workshops, presentations to City Council, and outreach at events, we built relationships with Pasco residents and those invested in its success. These relationships have been key in helping us implement the community’s vision.

Vision of a Cafe with Outdoor Seating

The Master Plan envisioned an empty building across from Peanuts Park as a cafe with outdoor seating.

Vision Realized: Cafe con Arte

Updates to parking regulations permitted the use of this building as a cafe. The then-empty building has now been transformed into a coffee shop, art gallery, and community space by local high school art teacher and artist Saul Martinez.

the master plan

Rather than a plan view drawing that outlines a preferred layout for new development, Pasco’s plan takes the layers of Downtown and its stakeholders and devises a set of strategies for making steps toward attracting the investment of both money—in public private investments into buildings, businesses, and public space—and time— by encouraging people to spend time in Pasco’s Downtown. Four key visions guide a set of goals and strategies for improving public ways, attracting and guiding private investment, and developing collaborative and sustainable infrastructure for the care and management of Downtown.

For example, the vision of “Active + Safe Streets for All” means programming Peanuts Park for more regular use, right-sizing Downtown streets to make room for bike lanes and wider sidewalks, improving lighting, introducing parklets and other uses of public space, and creating a wayfinding program. These distinct approaches all contribute to streets that are regularly used for a variety of activities, which help people feel safe and comfortable using public spaces.

Visions, Goals, Strategies

Pasco’s Downtown Master Plan was designed to be actionable, with a matrix of action items that correlate with community-formed goals for the future of Downtown.

Implementing the Downtown Plan

After the Plan’s adoption in January 2024, the City hired us on to help make it happen. One of the first things we did was to update the municipal sign code to allow full scale murals on Downtown buildings. Murals were previously treated as signs and allowed to occupy only 25% of a building façade, limiting what people could create and causing tension around the removal of murals that did not meet this requirement.

Murals made sense as a place to start because of the priority residents placed around expressing Pasco’s culture and bringing more art Downtown. They also serve as way to revamp buildings and signal that Downtown is a place that is celebrated and taken care of. While in many cases, redevelopment and infill are not feasible, revamping existing buildings with murals is a relatively low-cost and low-barrier way to start investing into Downtown and breathing life into the public realm.

The City’s Arts Commission is now distributing grants to local businesses to commission murals on their buildings. There is a simple review process for murals concepts, which allows the City some amount of control, while overall leaving the vision up to the artist and the shop owner. So far the City has received two applications and murals are already underway!

Mural underway!

A new mural project commissioned as part of the Arts Commission’s grant program.

maximizing the use of downtown public space

Another strategy for accomplishing the Downtown vision was to “Update Codes for an Active Downtown.” This meant looking at ways that codes could encourage active uses of public space including food trucks, parklets, and events. With parking an issue that many brought up during the public engagement process, this also meant evaluating parking capacity and occupancy to make sure that these new uses of space didn’t impact people’s ability to park close to their Downtown destinations.

Before we made these code updates, food trucks in Pasco were prohibited from being within 400 feet of schools or 300 feet of restaurants or cafes, and had to move every hour. This made it infeasible for many mobile vendors to locate downtown, preventing them from activating space by offering destinations for food and drink within the public sphere. Food trucks have history in Pasco, and in general (beyond Pasco) there are opinions about whether they pose a threat to their brick-and-mortar counterparts. But in the end, Council agreed that imposing fewer restrictions on where and when food trucks can vend in public space would help to activate Downtown, support local businesses, and serve as another venue for sharing Pasco’s culture.

Council also approved updates to code to allow the conversion of parking spaces into café seating for use by adjacent bars and restaurants. This measure, popularized during Covid-19 lockdowns, offers businesses more space for seating while also bringing more people into the public realm. It is also a chance for businesses to get creative, adorning their “street cafes” with decorative lighting, flower boxes, or colorful fencing that can add the much-craved and ever-elusive “character” to a neighborhood.

Bringing mobile vendors downtown

Prior to code updates, mobile vendors couldn’t locate within 400 feet of schools or 300 feet of other bars, restaurants, or cafes.

Lighting, Safety, Activation

Vibrant public space hinges on people being out and visible, which also helps increase feelings of safety through those additional “eyes on the street” (in the words of foundational urban planning voice Jane Jacobs.) Fittingly, concerns around safety and a desire to see more events and activities downtown were both brought up during early public engagement efforts. Respondents also indicated a related desire for more and better lighting.

We wanted to learn more about how Downtown lighting could improve, so we organized a “Night Walk,” which was attended by police, councilmembers, City staff, and other Pasco residents. The group walked several blocks, observing both gaps in lighting and an abundance of bright security and roadway lights. While lighting wasn’t egregiously absent, there were clear ways that more consistent lighting with more character and quality would improve the experience of visiting Downtown Pasco at night.

Night Walk

Gathering people for a night walk allowed us to assess conditions and talk to people about their visions for better lighting Downtown.

While we fancy ourselves a team that can roll up our sleeves and learn something new, we decided to bring in some experts to help us outline a plan for illuminating Downtown. We worked with Blanca Lighting Design, who devised a strategy for adding lighting to storefronts, alleyways, and “gems”—historic buildings, public spaces, and other features that make Downtown Pasco unique. The Blanca Lighting Design team selected a suite of low-maintenance, high efficiency, and aesthetically pleasing fixtures that the City can use to fill in lighting gaps and create a nighttime streetscape that is legible, while still eclectic.

Because lighting is an ingredient that on its own will not fundamentally change the way Downtown functions, we also built a suite of activation strategies into this plan, which we have dubbed LAS Luces: Pasco’s Lighting, Safety, and Activation Plan. These activation strategies will focus on streamlining an events program to make best use of Peanuts Park and create a regular schedule of activity that can reliably draw people downtown.

Lighting, Safety, Activation

Pasco’s lighting plan aims to set the stage for a vibrant nighttime streetscape by adding layers of lighting to storefronts, historic buildings, and the street.

What's next

To determine how to move forward with our next year of implementation efforts, we met with residents, business owners, and City Council to get their feedback. During meetings, people brought out the Downtown Master Plan book, pointing to images and asking “how do we get this done?” They voiced a desire to see the Lighting Plan implemented, the need for increased capacity for City-run events, and the potential to redesign City-owned buildings and spaces Downtown to better support business growth, recreation, and community.

Currently we are working with the City to outline its top priorities. We hope to cross many things off the list: installing new light fixtures downtown, creating a regular events calendar, proposing designs for making the best use of new City-owned property…there is still much to be done! We are honored to move forward working with the City of Pasco to implement their vision, and we are continuously inspired by those who are invested in making Downtown Pasco a unique and beloved destination.

Written by Hope Freije @Framework

SDf 2024 - seattleites find belonging in third places

Third places are glimpses into understanding how we build community in cities. For us at Framework, our 2024 Seattle Design Festival (SDF) installation starts a larger exploration of how urban planners and designers can foster “civic soul,” third places often being the places where this soul grows and thrives.

On August 17th and 18th, 2024 we displayed our installation “Postcards to Third Places” at Lake Union Park as part of the SDF. Over two days, we invited the public to share their appreciation for their favorite Seattle third places – the gathering spaces and incubators for art, creativity, and community care that are essential to urban life in Seattle. We wanted to get the community talking about our favorite local third places, express the value these places bring to our community, and offer people a way to share some love with their third places.

For a deeper discussion on the concept that inspired our installation, check out our last blog post.

Postcards to Third Places

Our installation for Seattle Design Festival 2024 asks visitors to write postcards to local community hubs.

An evolving installation

Throughout the weekend, visitors hung their postcards for all to see.

designing our “third place”

Our installation aimed to create a temporary, homey space for hanging out, having dialogue, and reflecting on the impact of third places in our lives.

The construction of the installation was an opportunity to work sustainably and promote Seattle-based third places in the process. Donated from Ballard Reuse, recycled doors formed the base of our installation. The doors displayed postcards designed by the public during the festival and framed a temporary “third place” environment.

We risograph printed our postcards at Paper Press Punch, utilizing a unique printing method that made each of the postcards special with a hand-printed and tactile quality. Festivalgoers could decorate their postcards with custom stamps, drawings and stories of what made their favorite third place special to them.

House of Doors

To build our installation, we repurposed doors donated from Ballard Reuse. We love that the mix and match style of doors speaks to the character that develops in third places over time. Together, the doors attached together create a temporary, mini-third place, a place where Seattle Design Festival goers could gather and write postcards to their beloved community hubs.

Where are our third places and what do they mean to us?

Over two days, the public wrote and decorated over 200 postcards in appreciation of their favorite spaces for food & retail, outdoor and indoor recreation, arts & culture experiences, and community resources like libraries and religious spaces. Amongst the most popular third places were Elliot Bay Book Company; the Ballard Farmer’s Market; Garfield Play Field; Schultzy’s Bar and Grill; Magnuson Dog Park and many of the Seattle Public libraries.

Throughout the festival, we had conversations with individuals who helped us understand what value third places bring to their own lives, and what makes these places essential to the community. Here are some highlights:

Third places can be places of respite, providing safe and comfortable spaces to unwind and relax. Some Seattleites have found these spaces in independent retail spaces, like the “Relaxation that comes from going through old records and CD’s” (written to Al’s Music Video & Games, U-District). Others in community spaces where they can be active. For one festivalgoer, the Central District’s Meredith Matthews East Madison YMCA is, “the perfect place to go when [they’re] overwhelmed, and the place to swim with [their] best friends.”

In our changing climate, respite is coupled with the need for refuge from extreme weather. One participant mentioned, “I work from home but when it gets too hot, I have to go elsewhere.” For this reason, they’ve found much-needed relief at Stoup Brewing in Capitol Hill.

Engaging with kids

Seattle Design Festival draws a lot of families, and we wanted to make sure our activity was kid-friendly. We created stamps that allowed people of all ages to customize their postcards.

Being Creative Together

Seattle Design Festival attendees sat at a cafe table and customized postcards.

One third of postcards were written to outdoor recreation spaces around Seattle, which included public parks, streets and plazas and natural areas. Appreciating natural beauty is often a primary value to Seattle’s favorite third places - like at Elliot Bay Park, on the Expedia Campus, where Seattleites go “to watch sunset and picnic and spot some seals.”

What often emerged from our conversations, was the issue of equity in third places: Who can access certain third places? Who cannot? And how does accessibility and inclusivity shape our favorite Seattle third places? With nearly 40% of the postcards written to private food and retail spaces, the issue of privatization and accessibility in third places is at the forefront. Access to these third places requires you to spend money, and may discriminate against the unhoused and otherwise struggling.

However certain third places were recognized for countering this status quo. “The affordability of donation-based and free Sundays and exposure for art students and art at large,” makes the Henry Art Gallery in U-District a preferred third place for many. In a similar vein, places like the KEXP Gathering Space are celebrated for cultivating inclusive environments for working and gathering, as described by one festivalgoer. Third places are spaces of belonging and interacting with our diverse community, especially for members of marginalized populations who might face difficulty finding solace in their daily routines.

Crunching the numbers

Different colored postcards corresponded with different third place types: Food & Retail (cafes, bookstores, markets, etc.); Outdoor Recreation (public parks, streets and plazas, natural areas etc.); Arts & Culture spaces (music venues, art & science museums, performing arts, etc.); Indoor Recreation (public pools, fitness studios, roller rinks, etc.); and Community Buildings (libraries, community centers, religious spaces etc.).

Mapping third places

In addition to writing postcards, visitors to our installation also pinned their favorite third places on a map of Seattle.

What remains clear is that Seattle third places are meaningful spaces for building community, whether that means running into familiar faces, meeting new friends, or serving as a central meeting point or neighborhood watering hole. At the Rainier Beach Community Center, an educator appreciates the opportunity to unexpectedly, “run into [their] students and their families.” Another participant mentioned how they, “met a whole group of friends [at the Seattle Bouldering Project] while climbing every Sunday”. In Downtown Seattle, Inside is a transformative arts studio and event space, and one postcard writer’s “favorite place to build community and to feel like [they] belong.”

Ultimately, a third place is somewhere we feel cared for - “Thank you for always being welcoming and taking care of me and my bike” someone writes to Good Weather Bicycle & Repair Shop, in Capitol Hill.

Framework team members relax after assembling the installation.

Written by Leila Jackson @Framework

postcards to third places

As Urban Designers and Planners, we’ve spent a lot of time recently thinking about how cities in Washington can prepare for the population growth that is expected to occur in the next 20 years. Front and center in these conversations are elements like land use, housing, transportation, and other infrastructure that makes the city tick. But when we talk to cities about their goals, it’s often the intangibles that weigh heavy on their visions for the future–“a city with character,” “a vibrant community,” “a thriving metropolis of arts and culture”…

At the same time, we’re seeing conversations about the disappearance of third places and the trend towards loneliness and disconnection from community. As cities like Seattle grow, rising rent prices and the pressures of development can squeeze out places that act as vital hubs for art, culture, connection, and community. This loss is apparent through projects like Vanishing Seattle, “a media movement that documents displaced and disappearing institutions, small businesses, and cultures of Seattle - often due to development and gentrification - and celebrates the spaces and communities that give the city its soul.”

The disappearance of third places is not unique to Seattle, nor is it a new issue. As far back as the 1990s, Sociologist Ray Oldenburg was recommending that urban planners course correct away from the disparate suburban pattern designed to “protect people from community rather than connect them to it.” He argued that people need third places–or places outside of the home (“first place”) and office (“second place”). These neighborhood hubs, he wrote, are vital for fostering civic engagement, creating webs of mutual aid, and allowing people to experience the “joy in living” that comes from enjoying the company of those who live and work around you.

Postcards to Third Places

Our Seattle Design Festival installation will invite visitors to customize a postcard for a beloved community hub.

Nurturing our third places

It’s hard to imagine a “vibrant” city that doesn’t have third places. Meeting new people, exchanging ideas, creating together… It all requires space, not to mention the need for a public realm that allows people to put the fruits of community on display. So why are these qualities so hard to plan for? Why, decades later, are we facing the same problem?

Sometimes we try to solve problems with data: Can we quantify the economic benefits of a third place? Can we convince decision makers that protecting community does indeed pencil out? Can we determine a third place formula that can be modeled, replicated…?

Sure, maybe. But if third places teach us anything, it’s that community solidarity is a powerful force. So what if we started by talking about our third places, learning about the places that other people hold dear, and sending those places some love?

The vision

Using recycled doors and cafe tables, our installation aims to embody the spirit of a third place, where DIY elements signal community participation in a space, and add beloved character.

Seattle design festival

Postcards to Third Places is an installation that invites participants to “send love” to their beloved community hubs in the form of a risoprinted postcard. This project will debut at Seattle Design Festival, where we’ll carve out our own temporary “third place,” an installation made of recycled doors and cafe tables. Visitors will customize their postcard and mark the location on a map, telling a story of the places that Seattlites hold dear. Finally, we’ll send the postcards out, a small act of love for these community institutions.

This festival won’t be the first or last time we contemplate how urban planners can advocate for and create cities that allow culture to thrive. After the festival, we hope to connect with many of these Seattle third places to learn more about how they’ve survived the pressures of the last decade. Stay tuned for blog posts with interviews with these community institutions, and reach out to us if you know someone who we should get in touch with!

Creating our third place installation

Donated from Ballard Reuse, recycled doors form the structure of our third place installation, and will be used to display postcards created by guests..

Written by Hope Freije @Framework

How to fund a park (in Washington)

I know it, you know it: parks can transform the way we experience living in and visiting urban areas. The data is on our side, with an abundance of studies touting the benefits to having access to parks: people exercise more, enjoy better mental health, and visiting parks regularly makes people more productive (cha-ching). Access to parks increases social cohesion, improves the air quality, and helps mitigate the effects of, you guessed it, climate change (NRPA). But if having friends, clean air, and a habitable planet doesn’t do it for you, rest assured that parks are also economically beneficial–from reducing flood risk to generating revenue through events, the NRPA reported that in 2021, local park and recreation agencies contributed an estimated $201.4 billion to the US economy (NRPA).

As cities in Washington gear up for a denser future, the way they invest in parks will play a role in how livable our new urban landscapes will be. Will we prioritize open plazas that provide relief between taller buildings? Will we create corridors that allow us to move through the city without cars? Will we set up programs that allow youth, the elderly, and everyone in between to find movement, enrichment, and community?

We fully support a future of robust parks, trails, and open space systems that not only provide respite from urban areas but are woven into its fabric. But dreamers as we may be, we know that this vision requires resources in order to implement. As crucial as they are, parks compete for city budget with other needs like housing, education, and transportation, and funding them may not always be a city’s top priority.

In our work with Washington cities on their comprehensive plans, arts plans, downtown plans, and parks, recreation, and open space plans, we are always thinking about how cities can access new funding sources while making the best use of the resources they currently have. Today we want to focus on parks, and the funding mechanisms available to Washington cities for building, maintaining, and programming them. The sources they choose can impact which projects get built and who benefits from the money, so today we’re breaking them down and using our office locale of Seattle as an example for talking through how these sources can be leveraged.

Volunteer Park, Seattle

A bespoke stage designed by ORA Architects brings people out to picnic and enjoy summer concerts in Capitol Hill’s Volunteer Park.

How much does Seattle spend on its parks?

Seattle’s 2024 budget allocates $226.03 million of the City’s operating budget for parks and recreation. This goes towards maintaining and operating the parks, as well as “golf course programs,” “zoo and aquarium programs,” and several other categories, which are listed on the 2024 budget website. Within the Capital Budget, there is a proposed $102.51 million going to parks, with about half of that going to Fix it First, the program that allows residents to alert the City of needs for repair, removal, cleaning, etc. This is more than the City has spent in previous years, with an operating budget of $163.35 million in 2019. It’s also higher than what the National Recreation and Park Association reports as the median operating budget of $28.88 million for cities over 250,000 in size.

Seattle values its parks. Its investments over the years have yielded parks that act as destinations for tourists and residents, grant access to stunning natural features, and serve as neighborhood hubs for recreation, gathering, and events. The budget described above consists of multiple sources, with the majority of the operations budget coming from the General Fund, meaning that Seattle is using taxes, parking fines, and other fees to fund the maintenance of its parks and facilities. Below, we describe other ways that Washington cities can fund their parks.

Bonds and Levies

Local governments can issue bonds or levy property taxes to fund parks and recreation, calling on local property owners and other residents to pay into these systems. These options typically require voter approval, meaning that the public has to believe that parks are valuable and that it is the constituents’ responsibility to help fund them. It also means that cities with wealthier residents and higher property values will accrue more funds to put towards creating and maintaining parks and recreation facilities than less affluent communities.

In 2008, community groups and citizens in Seattle helped pass the Parks and Green Spaces Levy, which awarded $146 million over six years to fund green spaces, neighborhood parks, and playfields. Under this levy, property owners paid $0.20 per $1,000 assessed value, so the owner of a home valued at $500,000 would have paid $100 annually. As a homeowner, the benefits of having parks in your neighborhood are significant, both because of the benefits of being able to access the parks yourself, and from the associated boost to your home value. It’s fitting, then, that property owners would contribute to the maintenance and expansion of their local parks.

While the Seattle Parks and Green Spaces levy has ended, the King Country Parks Levy was renewed in 2019, which costs homeowners about $7.60 per month if their property value is assessed at $500,000 (King County Parks Levy). Because this levy is countywide, it means that homeowners are paying into a fund that benefits people in all corners of King County, allowing residents in less wealthy areas to benefit from the resources of the most affluent. In a county growing increasingly interconnected, it makes sense to share the responsibility of funding parks across municipal lines.

Cal Anderson Park, Seattle

Cal Anderson hosts dozens of unique uses from spike ball competitions, skateboarding, and mobile vendors.

Park Districts

Washington allows for the formation of Park and Recreation Districts, Park and Recreation Service Areas, and Metropolitan Park Districts, which act as municipal corporations or quasi-municipal corporations that can levy property taxes, issue bonds, and generate other revenues for park purposes. Between the three types, there are differences in how they function, how they are initiated and governed, and how they can implement levies (MSRC), but your attention span is too precious to waste on those details at this moment.

The first Metropolitan Park District was formed by Tacoma in 1907, which still exists today. In 2014, Seattle voters passed Proposition 1, which created the Seattle Parks District, which has the same boundaries as Seattle and is governed by Seattle City Council under the advisory of the Board of Parks and Recreation Commissioners (City of Seattle). Seattle Parks District collects property taxes to fund park maintenance, operation, and development, and is the top contributor to the 2024 Capital Budget for parks funding (49.7%) and the second greatest source of operating funds (29.09%) for the operating budget (Seattle Open Budget).

Impact Fees

What can cities do if their constituents vote against property taxes and levies to fund parks? In Washington State, cities and towns planning under the Growth Management Act can use impact fees charged to developers to fund some park expenses. These one-time fees are designed to address the need to expand public facilities as a population grows. Essentially: “You are bringing more people to the city because you built them a place to live, and made money off of it, so you need to share the burden of providing those people with infrastructure.” Developers are charged fees based on the size of the unit(s) they are building, the funds from which can be used to fund roadway projects (including bike lanes and sidewalks), parks, schools, or fire protection facilities. By law, park impact fees can only fund system improvements listed in the Capital Facilities Element of an adopted Comprehensive Plan (MSRC), meaning the money goes to projects that have been researched and vetted within the comprehensive planning process.

Cities determine a rate to charge developers that is based on the scale of what’s being built. For example, the City of Mercer Island charges $6,316 per single-family unit being built, and $3,933 per multi-family unit. Some cities have more specific rates, for example the City of Redmond differentiates based on building use (“retirement community,” “day care”) and neighborhood, which may allow them to discourage or encourage certain types of development–for example, to build a car wash downtown you will pay nearly $20,000 per stall in impact fees (The Urbanist). The City of Everett calculates rates based on the number of bedrooms in the unit to better reflect how many people the new building will add to the population. Some cities also charge impact fees for commercial and industrial construction, with the idea that people who come to a city to work also benefit from access to parks.

While this strategy addresses the increased infrastructure needs that inevitably coincide with population growth, it puts this burden on the developers, impacting the feasibility of building new and needed housing. While developers don’t make the most sympathetic protagonists, they are the ones up to bat to produce much needed housing stock, and are only going to build it where and when the numbers make sense for them. Some housing advocates argue against impact fees for this reason.

The issue of whether to enact impact fees in Seattle arose this past year–in 2023, City Councilmembers Alex Pedersen and Lisa Herbold proposed amending Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan to include details on how a transportation impact fee would be implemented, but the initiative was appealed and council has not moved forward on it (The Urbanist). While there is a question of how to maintain transportation funding in the wake of the nine-year transportation levy called Move Seattle, many argue that it is irresponsible to discouage new development at a time when the area is experiencing a housing crisis. Park impact fees were not part of this discussion and are not used in Seattle.

RCO and Other Grants

The Recreation and Conservation Office is the state agency that manages grant programs to distribute funds for park, trail, recreation, and habitat restoration projects. They are a small agency (53 employees) with a sizable budget (4th largest capital budget of any state agency), and since 1964, they have awarded more than $2 billion in grants to cities, tribes, districts, and other organizations throughout Washington (RCO).

To be eligible for many of these grants, organizations need to have a Parks, Recreation, and Open Space Plan (PROS Plan), which outlines existing conditions, future needs, and goals for their park system. Within these plans, they also delineate a Capital Projects list, which outlines what projects they plan to invest in, what the priority level is, and how much it may cost. Once a plan is approved, that organization is eligible to apply for grants for six years. These plans can be costly to produce, though some cities receive grants to fund the initial planning effort.

These grant opportunities allow motivated park department staff and others to secure funding for the projects their constituents and they want to see completed. There are several types of funds available for acquisition, maintenance, or development of parks, trails, or athletic facilities. They are, however, highly competitive. Some are also restricted to areas that lack recreational opportunities, have underserved populations, and possess limited financial capacity. For a small town with few or no full time employees dedicated to the parks, pursuit of these grants can be time-exhaustive and may not pay off.

In 2022, Seattle was awarded RCO grants that funded projects at Rainier Beach Playfield Skatepark, Little Brook Park, Soundview Playfield, Colman Pool, and others.

Elliot Bay Trail, Seattle

Trail Users enjoy a clear view of the water on the Elliot Bay Trail, which passes through Olympic Sculpture Park, Myrtle Edwards Park, Centennial Park, and Elliot Bay Park.

“Friends of” Groups

While the National Recreation and Park Association reports that most park agencies draw the majority of their funding from taxpayer support and park facility revenue (i.e., registration fees, concessions), 73% of park and recreation leaders place a high degree of importance on fundraising support they receive from park foundations (NRPA). Often named as “Friends of” the park, these groups can form to support an entire park system (as in the Seattle Parks Foundation) or be focused on a certain park or area (like the Volunteer Park Trust or the Freeway Park Association). These nonprofit park partners can offer support in many ways, but their ability to fundraise given their 501c3 status, and therefore to generate funds outside of grant or budget cycles, is seen as their most vital function.

While park leaders report that their relationships with these organizations are most successful when they align on goals and communicate regularly , “Friends of” groups are not beholden to parks departments or governing bodies to dictate what parks projects they raise funds for. Their support may thus not be reflective of the goals of the park department or what is laid out in the parks plan. Further, it may be easier to raise funds for projects in wealthy neighborhoods, therefore perpetuating cycles of inequity (NRPA).

How Should Parks be Funded?

At the end of the day (or fiscal year as the suits say), the park funding sources most suitable for a city depends on the values and resources of its constituents, the city’s desire for growth, and the capacity of the parks department. Impact fees only account for growth, thus cannot be relied upon as a funding mechanism. Grants are competitive and may not apply to your organization’s demographic or specific project. Nonprofit partners can be useful, but require close collaboration with parks departments and may not accomplish park department goals in an equitable manner. The only reliable way to fund a parks system is for the city and its constituents to consistently devote resources to it through taxes, levies, bonds, and other such measures.

The benefits of parks within urban environments are vast, and increasingly important as Washington’s city’s gear up for a denser future. The mitigation of the Urban Heat Island Effect provided by trees and planted areas, the health benefits enjoyed thanks to access to nature and recreation options, and the impact to culture that gathering spaces afford are tantamount for growing cities. And thanks to a myriad of academics, we can also confidently say that these health, climate, and cultural benefits also make cities money (NRPA). The decision to invest in parks is thus precisely that–an investment. Whether cities go all in on a waterfront park, focus on improving access to neighborhood parks, or use their resources to maintain robust indoor facilities, we hope that cities and their constituents will recognize their parks as vital infrastructure and fund them accordingly.

Written by Hope Freije @Framework

Kids, joy, and flipping the table on who gets to influence the future

It turns out the next generation has a clear idea of what they want for society and the planet. As planners and urban designers, it’s up to us to create new avenues for youth engagement and to advocate for kids’ influence on decision-making. At Framework, we’re proud of our approach to youth engagement in a variety of projects and look forward to giving kids more of a role in the future.

Traditional engagement efforts in community planning play to the strengths of people with an abundance of time and access to information. Night meetings at city hall, public hearings, and prototypical focus groups revolve around the nine-to-five work schedule and assume people can break away from their life obligations around dinner time. A check-the-box mindset on public engagement too often defaults to these perfunctory outlets and the result amplifies the voices of older and wealthier residents. This is frustrating, because it ensures that the narrow interests held by this subset of the population become the basis for decisions affecting entire communities. Consequently, the ideas and aspirations of people of color, low-income residents, renters, and kids are lost, or, at best, underrepresented and underappreciated.

This doesn’t have to be the endgame of public discourse in urban design and planning. Luckily, many cities are increasingly aware of the existing engagement deficits and are looking to connect with a wider range of people that more accurately represent the community at large.

As a firm that puts people at the heart of planning and design, Framework has maximized inclusive engagement since our earliest projects. And over the past year, we’ve turned it up a notch when finding creative ways to emphasize the voices and ideas of one of our most overlooked groups in society: kids.

First, our honest appreciation for kids

Children, teenagers, and young adults inherently see and experience our communities differently. Not only are they incredibly insightful about the issues that adults have been trying to solve for decades, but they bring a perspective of joyfulness and scale that’s often challenging for jaded, full-grown adults to fathom. Unleashing their ideas, however, requires much more thought than asking them to speak up during a city council meeting.

Here are a few examples of how we’re putting kids’ perspectives at center stage in our projects.

Seattle Design Festival – Design Your Own Neighborhood

Last summer, Framework developed a fun kid-friendly activity for the Seattle Design Festival called “Design Your Own Neighborhood.” Our installation invited festival-goers to create an inclusive neighborhood that supports community gathering, maximizes green/open space, and accommodates a variety of homes, retail/service offerings, and public amenities.

Anticipating the masses of families that would descend upon Lake Union Park in mid-summer, we intentionally designed the activity with kids in mind. Our components—a gridded ground cloth and colored boxes indicating homes, retail, and amenities—were simple and small so children could easily maneuver and place their buildings. Plus, the flexible, yet gamified rules spurred creativity and even instilled some competition among these young designers. Our favorite outcomes, however, were kids’ narratives of their creations.

Comprehensive Planning in Milton and Sultan – From Crayons and LEGOs to Visual Preference Boards

Youth engagement is essential in our comprehensive planning projects. As we envision the next 20-years in cities across the state, we’re especially diligent about kids’ involvement as demand for more kid-focused activities and destinations intensifies in many communities. It’s also clear that kids are keenly aware of the community needs for 30-to-40 year-olds—their age by the end of the planning period.

In Sultan, we rolled out a huge vinyl basemap and invited kids (and their parents) to scribble notes and place LEGOs to indicate where they want to see new homes, schools, shops, restaurants, parks, trails, and safe streets. The activity—inspired by James Rojas’ Placeit concept—is approachable for many ages and abilities, place-based and aspirational, and interactive at many levels: someone can place a single LEGO or have a detailed discussion with us about their ideas.

We’re also visiting schools and tying into other events that teenagers are already attending. In Milton, we asked middle schoolers to map their favorite places and dream about new destinations. We also had the opportunity to gather specific design ideas for Hill Tower Park, which gave us invaluable information about kids’ desired programming like a climbing structure and splash pad.

Arts and Culture in Renton – Wishing Wells and High School Surveys

Framework is also involving youth in our arts and culture plans. In Renton, we asked kids to toss their wishes for new public art projects, cultural spaces, and more into a makeshift wishing well—in exchange for a piece of candy, of course! We also had the opportunity to join an art teacher’s event where high school students felt comfortable filling out a survey about new creative classes, performance spaces, and art installations in the city.

Let’s Face it: Planning for kids is planning for the future

If we really want safer streets, equitable development, diverse housing options, and vibrant public spaces in our communities, then we ought to elevate the perspectives of children. Kids approach the built, social, and natural world with a balance of curiosity, imagination, and vulnerability that can be equally practical and inspiring. They’re regularly looking for adventure and play, and, at the same time, undeniably vulnerable to the harms of a warming climate and an unsafe, inaccessible public realm—not to mention entirely disadvantaged in a culture that revolves around cars. Our youth are also keenly aware of our societal struggles for social justice and climate action. So, taken seriously, the realities of kids’ lived experience can inform design interventions and policy moves that produce a more comfortable, joyful, and socially just world for everyone.

As our work progresses, we’ll be constantly looking for more opportunities to engage with these thoughtful and imaginative members of our society.

Written by Tyler Quinn-Smith @Framework

Seattle and Bilbao: What can we learn from each other?

In an urbanizing world, cities around the globe are building new, denser neighborhoods. The quality of life in expanding cities is can and should be shaped as humane places that support the well-being of individuals and society. Framework’s Lesley Bain shares some thoughts from an American perspective as she headed to Bilbao for a conference on how organizations around the world are finding innovative ways to support the creative sector.

STORY 1

What is the value of sharing ideas between evolving cities?

STORY 2

Transforming neighborhoods —a pattern from industrial to creative to monoculture

STORY 3

The quality of the street level is critical, where public life and connections to nature create well being

STORY 4

How do you center humanity in a neighborhood created from the top down?

STORY 5

Seattle created the Cultural Space Agency as a needed mechanism to support cultural space

STORY 6

The necessary question of what culture, whose culture are we trying to support?

STORY 7

Hopes for a discussion on creative culture with people from around the world

Recorded by Lesley Bain @Framework

pda to save arts + cultural spaces in seattle

photo by Joe Iano

Last month, Mayor Jenny Durkan signed the Cultural Space Agency Public Development Authority charter, the first to be launched by Seattle since 1982. It is the first to be proposed, ever, that is directly controlled by the community it will serve, aiming to create direct and literal community wealth.

A Public Development Authority (PDA) is a quasi-public mechanism allowed in the State of Washington to accomplish public goals. This ambitious idea will be a game-changer for the ability to maintain and add to the city’s cultural spaces. Margo Vansynghel, a reporter for Crosscut, reflects on how “the end goal is to make sure that cultural organizations can actually own the buildings and spaces they occupy as the ultimate protection against displacement.” Read the full article here.

The Cultural Space Agency PDA is one of the ideas to come from Framework’s collaboration with the City of Seattle Office of Arts and Culture. The multi-year, multi-pronged Staying Power Project set out to support space for arts and culture in a city where displacement has been exponential and communities of color have been disproportionately hurt. Starting with The CAP Report: 30 Ideas to Create, Activate and Preserve Space for Arts & Culture, local developers, arts organizations, designers and building officials helped break down why cultural spaces were not being included in new development and propose how barriers in creating art space could be removed. The follow-up study Structure for Stability explored the creation of an independent real estate entity that partners with community organizations to hold and preserve affordable arts and cultural space.

Staying Power received the Award of Merit for Research & Innovation at the 2020 AIA Seattle Honor Awards. See the awards page and project highlights here. Additionally, The CAP Report received this past year’s Sustainability Award from the APA/PAW Annual Excellence in Planning Awards (full list of winners here).

Congrats to @seaofficeofarts and the whole project team!

For additional coverage of the PDA announcement, check out articles from The Stranger and Seattle Times.